The Second Punic War (218–201 BC) was one of the most decisive conflicts in ancient history, pitting Hannibal of Carthage against the Roman Republic. From the legendary Alpine crossing to the devastating Battle of Cannae, this war redefined military strategy forever.

What Were the Punic Wars?

The Punic Wars were a series of three devastating conflicts fought between Rome and Carthage from 264 BC to 146 BC for control of the Mediterranean world. These wars pitted the two dominant superpowers of the ancient world against each other in a struggle for supremacy that would determine the fate of Western civilization. Rome ultimately emerged victorious, but not before Hannibal Barca, one of history's greatest military commanders, brought the Roman Republic to the brink of collapse.

The First Punic War: Setting the Stage

Rome sought to expand its territory through Sicily, which was partially controlled by Carthage. This territorial dispute sparked the First Punic War in 264 BC. At the time, Carthage dominated the Mediterranean with its formidable navy, while Rome's strength lay in its undefeated land forces.

Initially, Carthage avoided land confrontations and focused on naval engagements where they held the advantage. However, Rome responded by building its own fleet and developing innovative tactics. The invention of the Corvus—a boarding bridge that turned naval battles into land-style combat—gave Rome a crucial edge. By 241 BC, Carthage was forced to sign a peace treaty, surrendering Sicily and paying substantial war reparations to Rome.

Hamilcar Barca: Father of Vengeance

Hamilcar Barca was a distinguished Carthaginian general who fought against Rome during the First Punic War. Bitter from Carthage's defeat, Hamilcar harbored an intense hatred for Rome. According to historical accounts, he made his young son Hannibal swear a sacred oath of eternal enmity against Rome. Hannibal reportedly declared, "I swear so soon as age will permit...I will use fire and steel to arrest the destiny of Rome." This childhood vow would shape the course of ancient history.

Hannibal: Rome's Greatest Enemy

Following the First Punic War, Hamilcar led an expedition to Iberia (modern-day Spain) to secure its valuable silver mines and rebuild Carthaginian power. When Hamilcar died in battle in 228 BC, his son Hannibal assumed command of Carthaginian forces in Iberia. True to his childhood oath, Hannibal would never befriend Rome.

Using wealth from Spanish silver mines, Hannibal raised a powerful army and began expanding northward. Rome watched nervously but couldn't intervene directly—the peace treaty allowed Carthaginian expansion south of the Ebro River (Iberus), and Hannibal had not yet crossed that boundary.

The Second Punic War Begins

The spark that ignited the Second Punic War came from the city of Saguntum, a Roman ally located south of the Ebro River in Carthaginian territory. When Saguntine forces attacked neighboring Carthaginian settlements and massacred their populations, Hannibal retaliated by laying siege to Saguntum in 219 BC.

Rome demanded that Carthage surrender Hannibal for punishment. When a Roman delegation arrived in Carthage, they presented the senate with an ultimatum: choose between war and peace. The Carthaginians deflected the choice back to Rome. The Romans chose war. This dramatic confrontation marked the beginning of the Second Punic War—a conflict that would last 17 years and test Rome's very survival.

Crossing the Alps: An Impossible March

Hannibal proved himself a military genius through his audacious strategy. Understanding that a direct assault would fail and that Carthage's weakened navy couldn't contest Roman sea power, he conceived a plan that seemed impossible: invade Italy by marching overland through the Alps.

The Romans considered the Alps impassable and left their northern frontier virtually undefended. Hannibal's expedition began with an impressive force of 38,000 infantry, 8,000 cavalry, and 37 war elephants—creatures the Romans had rarely encountered in battle.

The Alpine crossing proved devastating. Treacherous mountain paths, hostile tribal attacks, avalanches, and brutal cold claimed approximately half of Hannibal's army. By the time he descended into the Po Valley in 218 BC, only 20,000 infantry and 6,000 cavalry remained. All but one elephant had perished. Yet despite these losses, Hannibal had achieved what Rome thought impossible—he was in Italy, ready to strike at the heart of Roman power.

Taking the Fight to Rome

Upon reaching northern Italy, Hannibal immediately began recruiting Gallic tribes who harbored their own grievances against Roman expansion. Many joined his cause willingly. The Romans were shocked to discover Hannibal had appeared in northern Italy—they had expected to fight in Spain or Africa, not on Italian soil. Hastily assembling their legions, Rome prepared to confront the Carthaginian threat.

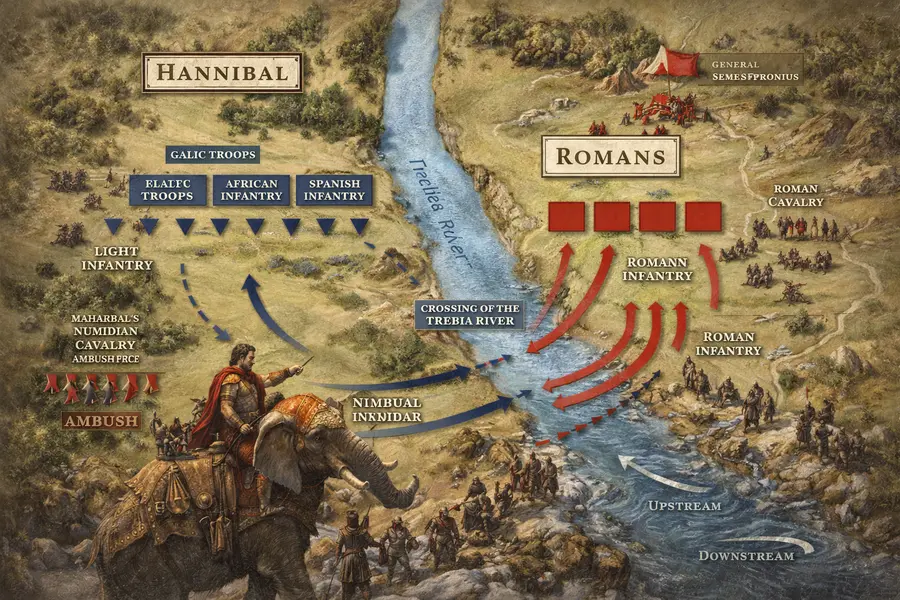

The Battle of the Trebia (218 BC)

The Battle of the Trebia marked Hannibal's first major engagement in Italy. In December 218 BC, near the banks of the Trebia River, Hannibal's 40,000 troops faced a Roman force of 42,000 under consul Tiberius Sempronius Longus.

Though outnumbered, Hannibal held crucial advantages: his troops were well-fed and rested, while he possessed superior cavalry. Using psychological warfare, Hannibal's Numidian horsemen taunted Sempronius with insults that enraged the impulsive Roman commander. He ordered his legions to pursue the Numidians across the freezing Trebia River.

By the time the Romans crossed, they were soaked, exhausted, and freezing—facing a fresh, well-prepared Carthaginian army. As battle was joined, Hannibal sprang his trap. He had concealed 2,200 elite troops under his brother Mago behind the Roman position. When Mago's force struck the Roman rear, panic erupted.

The result was catastrophic for Rome: approximately 26,000 casualties against Carthaginian losses of only 4,000-5,000. This stunning victory convinced more Gallic tribes to join Hannibal, significantly strengthening his army.

The Battle of Lake Trasimene (217 BC)

On June 21, 217 BC, Hannibal executed what remains the largest ambush in military history at Lake Trasimene. With 55,000 troops concealed in the surrounding hills, Hannibal lured the Roman army of 30,000 under consul Gaius Flaminius into a narrow valley along the lakeshore.

As the Roman column advanced through morning fog, they attacked what appeared to be a small Carthaginian force at the valley's end. Suddenly, Hannibal's hidden troops descended from the hills, trapping the Romans against the lake. It was a massacre. Rome lost 15,000 killed and another 15,000 captured, while Carthaginian casualties numbered only 1,500.

The Battle of Cannae (216 BC): Masterpiece of Destruction

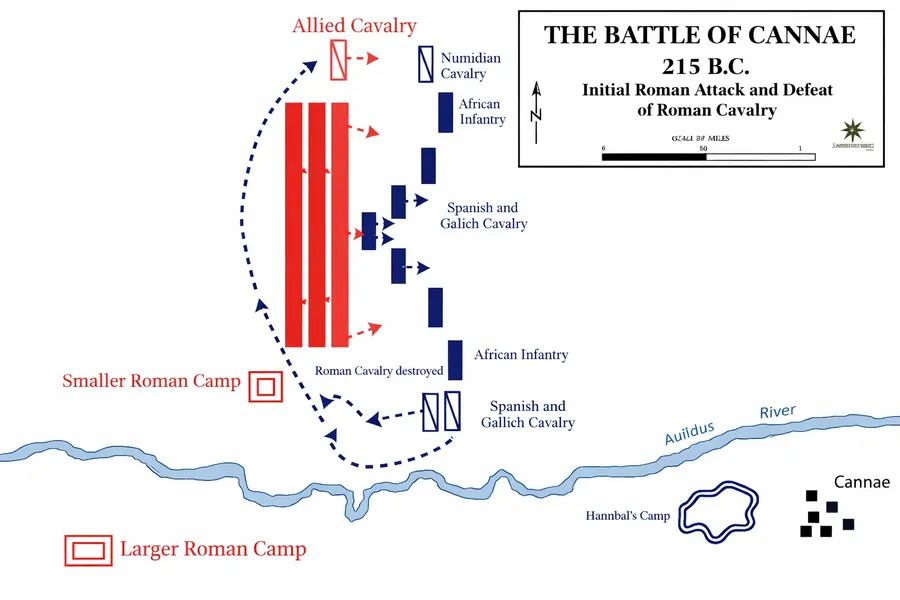

After the disasters at Trebia and Lake Trasimene, Rome adopted the cautious Fabian strategy—avoiding pitched battles and containing Hannibal through harassment and attrition. This defensive approach worked, but the Roman public grew impatient and demanded decisive action.

Rome assembled its largest army in history: 86,400 troops under consuls Varro and Paulus. On August 2, 216 BC, near the town of Cannae in southern Italy, this massive force confronted Hannibal's 50,000 troops. What followed became the most studied battle in military history—a textbook example of double envelopment.

Hannibal arranged his army in a crescent formation with his weakest troops at the center and veteran forces on the flanks. Varro sought to use Rome's numerical superiority to smash through the Carthaginian center.

As the armies clashed, the Carthaginian center slowly buckled backward under the Roman assault—but crucially, it did not break. Hannibal personally commanded these troops to maintain morale. Meanwhile, his veteran flanks held firm, and the Roman legions pushed deeper into what was becoming a trap.

As the Romans pressed forward, the Carthaginian flanks pivoted inward, surrounding them on three sides. Then came the final blow: Hannibal's superior cavalry, having routed the Roman horsemen, returned to strike the Roman rear. The encirclement was complete. What followed was a massacre in which the Romans lost 55,000-70,000 men. The Carthaginians lost a mere 5,700.

Rome Refuses to Surrender

The catastrophe at Cannae should have ended the war. With one-fifth of Rome's fighting men dead, the city faced potential collapse. Rome declared national mourning and, in desperation, even resorted to human sacrifices to appease the gods. Yet remarkably, Rome refused to surrender or negotiate peace. The Roman spirit proved unbreakable.

Hannibal, surprisingly, did not march directly on Rome. He lacked siege equipment and sufficient forces to assault the city's massive fortifications. Instead, he hoped Rome's Italian allies would defect—some did, but most remained loyal. Rome returned to the Fabian strategy, refusing Hannibal another major battle while simultaneously attacking Carthaginian holdings in Spain. The war in Italy became a grinding stalemate, but Rome remained determined to fight on.

The Battle of Zama (202 BC): Hannibal's Defeat

After years of stalemate in Italy, Rome brought the war to Africa. In 203 BC, Hannibal was recalled to Carthage to defend the homeland against Roman invasion led by Scipio Africanus—a brilliant commander who had studied Hannibal's tactics and learned from them.

At Zama in 202 BC, Hannibal fielded 40,000 troops including 80 war elephants against Scipio's 35,100 soldiers. The Romans possessed superior cavalry—a crucial advantage. When Hannibal unleashed his elephants, Scipio's troops blew trumpets and created corridors for the beasts to pass through harmlessly. The frightened elephants stampeded back into Carthaginian lines, causing chaos.

The battle ended in complete Roman victory with Carthage losing 40,000 troops, effectively ending the Second Punic War. Hannibal had finally met his match. He later went into exile and eventually took his own life between 183-181 BC, preferring death to Roman captivity. The greatest military mind of antiquity died far from home, having come tantalizingly close to destroying Rome but ultimately falling short.

Related Articles

Reference and Links

Second Punic War - Wikipedia - Hannibal Barca

Hannibal | Biography, Battles, & Facts | Britannica - Hannibal, Carthaginian general, one of the great military leaders of antiquity, who commanded the Carthaginian forces against Rome in the Second Punic War (218-201 BCE) and who continued to oppose Rome until his death.